Commemorating Johnny Sundstrom: A Voice for the Siuslaw

Since Johnny Sundstrom died on August 10th, the Siuslaw Watershed Council has been mourning the loss of more than just a cherished elder statesman. His vision was a vital force for restoration efforts; for decades Johnny stood at the center of the local conservationist network that he played such a key role in organizing. Known for his ability to build bridges and connect unlikely allies, Johnny was integral in defining the ethos at the center of the Council’s work.

He respected all forms of life in the watershed, from old growth trees and spotted owls to loggers and farmers, and his pragmatism and integrity could bring even the most distrustful stakeholders to the table. Though he had long ceded most of his conservation responsibilities to younger generations, his continued presence at meetings and events was a quiet reminder of his belief that conservation must be undertaken with the knowledge of what is at stake—that we have everything to lose, and everything to gain.

Johnny first got involved in local conservation after years spent dedicating himself to the home front. At Rock Creek Ranch, the remote Upriver property he and his land partners bought in 1976, he practiced intentional land management while raising a family. His greatest mentor during this time was the land itself, and he was eager to hone his vision by learning what it had to teach him.

One of his yearly highlights was watching the salmon runs from the creek that ran through his property. He loved to observe them at home in their habitat—“fighting, breeding, dying, coming home—all that’s fascinating,” he explained in a Siuslaw Watershed Council video. So when salmon populations started to decline, Johnny noticed right away. Knowing that losing the salmon would be catastrophic for the forest he lived in, he and his neighbors sought for ways to effectively advocate for their ecosystem.

But in his entry into conservation he set himself apart from the entrenched battle being waged throughout the 80’s between environmentalists and the logging industry. He may have set out to protect the deep woods that were his refuge, but he could also see how environmentalists alienated locals they needed as allies. His children went to school in Mapleton alongside the children of loggers, and as a rancher his approach to land management was far more practical than utopian. The folly of pitting the needs of the economy and the environment against one another was obvious to him. In his mind the question was how to align seemingly separate interests until the relationship between economy and environment became symbiotic.

It also didn’t hurt that before he settled in the Siuslaw Watershed, Johnny had spent the 1960’s acquiring a formidable track record of political conflict with the U.S. government. He saw no appeal in increasing federal environmental restrictions to the detriment of locals. Instead, he wanted to find creative solutions which made sense to the community, that they could execute themselves. As Johnny explained it, “The whole thing about collaboration is that if it’s done right, nobody gets everything they want but everybody gets something. And it’s got to be based on mutual benefit. Maybe not for this project, maybe not even for this year. But over time it has to pay off in some way for everyone.”

Johnny was as rooted in his community as it is possible for one person to be. But he was also a visionary whose impact spanned continents and crossed oceans. The walls of his home were lined with bookshelves—he read everything from Russian literature to the classic Westerns of Louis L’Amour. Johnny had always been a thinker. He was the rare individual whose eye for detail could also take in the bigger picture, and his conservation work was informed by deep contemplation. One of his favorite topics was the way place shaped the human experience, or as he succinctly put it, “people at home in a place.”

When the success of his conservation efforts made him a fixture at watershed restoration conferences all over the world, he was able to see this principle at work in the farthest flung locations. Everywhere he went, he looked for the place in the people and the people in the place, and what he found was a home nearly every place he went. His loss may be most deeply felt by members of his immediate community, but they are joined in mourning by his adopted family from the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming, his friends among Maasai herders in Kenya, and fellow conservationists as far afield as Australia and Northern Russia.

The years since his son Shiloh died in a 2015 hit and run were likely the hardest of Johnny’s life. The two were incredibly close. Shiloh had shared his father’s conservationist vision and taken it in new directions, and they understood each other in a way that appeared effortless. Shiloh’s death cut his father’s will to live to the quick. But even in the face of such incalculable loss, Johnny never lost sight of the bigger picture. He continued to tend to the conservationist network he had worked so hard to build, drew his community in even closer, and urged the next generations to take their place in the struggle for a better world.

In spite of everything, he remained a person at home in a place. Most evenings found Johnny sitting on his weathered porch at Rock Creek Ranch, watching the sunlight slowly disappear from the forested mountain ridge that served as his horizon line. From there, he loved to observe the comings and goings of his farm, from a scurrying flock of sheep to his daughter and granddaughter ambling hand-in-hand down the road. He relished the slow moments that let him listen to the land.

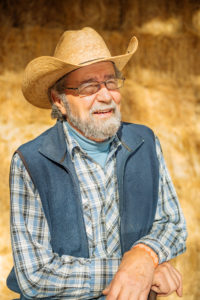

The world Johnny left behind will remember him for the thousand things he did and was—a storyteller, forest dweller, rancher, conservationist, thespian, revolutionary, man of letters, rainforest cowboy, and living bridge between all sorts of people with nothing in common other than having the good fortune to be in his fold. If the thought of filling his shoes feels daunting to those of us charged with continuing his legacy, that’s as it should be. There is no replacing a man with the character and gravitas of Johnny Sundstrom. The best we can do is to hold his vision close, carry on the work, and try everything we can think of to make him proud.

Written by Holly Devon for the Siuslaw Watershed Council